|

By: Amanda Charest The yacht “America” was an early clipper ship designed for speed. Her first captain, Richard Brown was born in Mystic, Connecticut on July 3, 1810. Destined to be a captain, he and four other boys in his town ran away as children to New York. There, the boys pursued their dreams of working on ships. All five became captains and Richard Brown later returned home as an adult, victorious. Being “America’s” captain during her victory in the Queen’s Cup brought him a good deal of fame.  Captain Richard Brown Captain Richard Brown Sadly, the other four boys were all drowned at sea and Captain Brown believed it would be his fate as well. However, that did not keep him from sailing. During his life, he sailed between 50 and 60 yacht races. He was known for his honesty and intelligence. He died at 75 years old after he was frostbitten while steering a ship into port on a particularly harsh winter night. The frostbite turned into gangrene, and he passed away on June 18th, 1885. Shortly after being built by the New York Yacht Club, “America” sailed to England to participate in the Royal Yacht Club Cup. The Royal Yacht Club Cup, hosted by the Royal Yacht Squadron, marked the first competition between American and English yachts. Racing against a fleet of 15 English counterparts, the America secured victory by a remarkable 18-minute margin, garnering significant attention for the vessel and its captain. Queen Victoria herself boarded the ship for inspection after the victory. The image below shows her congratulating John Cox Stevens, the ship’s owner. The win brought a new sense of sportsmanship between the recently formed United States and England. The win was immortalized in the lithograph by T.G. Dutton and based on a painting by O.W. Brierly. It was available for purchase on September 5, 1851. Such a historic win was bound to be a part of Bradley Barnes’s collection. The lithographs were widely produced and collected among maritime enthusiasts.  Over the next few years, the ship was used for racing until the start of the Civil War. During the Civil War, “America” was used as a blockade ship and briefly fell to Confederate use under the name Memphis. Not much is known of its Confederate usage. The ship's speed and ability to slip between ports, creeks, and rivers undetected contributed to its reputation as a sort of “flying Dutchman”. In 1862, the wreckage was found in Dunns Creek 70 miles above Jacksonville Florida. The ship was pumped free of water, plugged, and towed away for repair. It had sustained little water damage. After the yacht was repaired, it was returned to service blockading Charleston. After the war in 1866, “America” was put out of use for 3 years and became a school ship until the fall of 1869. Having spent over 30 thousand dollars in 4 years the government ordered the ship to be sold at auction in 1873. It was sold to General Benjamin Franklin Butler and was used from 1873-1892 as a recreational ship. In 1874 the ship returned to racing until General Butler's death in 1893. “America” was passed to his son Paul who was uninterested in sailing. Paul passed it to his nephew Butler Ames after the ship sat for 4 years. In 1897 the ship returned to racing briefly before war broke out with Spain. The ship returned to service until 1898 when the war concluded. The ship returned to racing until its last season in 1901. It was then put out of commission and sat idle until 1916 when it was put up for sale. Due to World War One, there was little market for pleasure boats. In 1917, the ship was sold, and its lead was sold for munitions production to aid the war. The decision was made to return the ship to the Naval Academy with the aspiration of preserving it for future museum use. On September 29, 1921 ship was docked at the Royal Naval Academy and was sold for $1.00 to Charles Francis Adams due to a law that the government could only receive property through sale or capture. “America” remained under its care until 1942 when the ship was scrapped due to damage during a snowstorm. The shed the boat resided in had collapsed under the weight of the snow. Despite the ship’s tragic demise the adventures and tales of this historic ship live on.

0 Comments

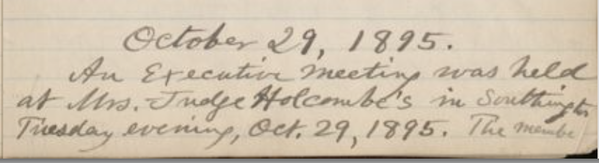

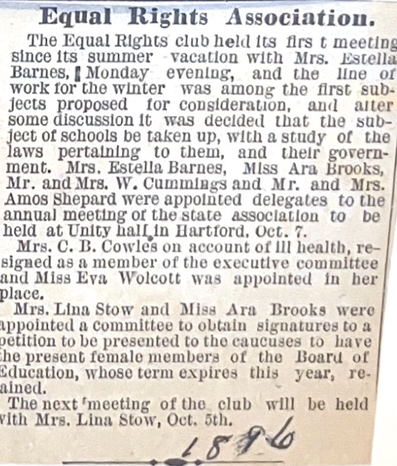

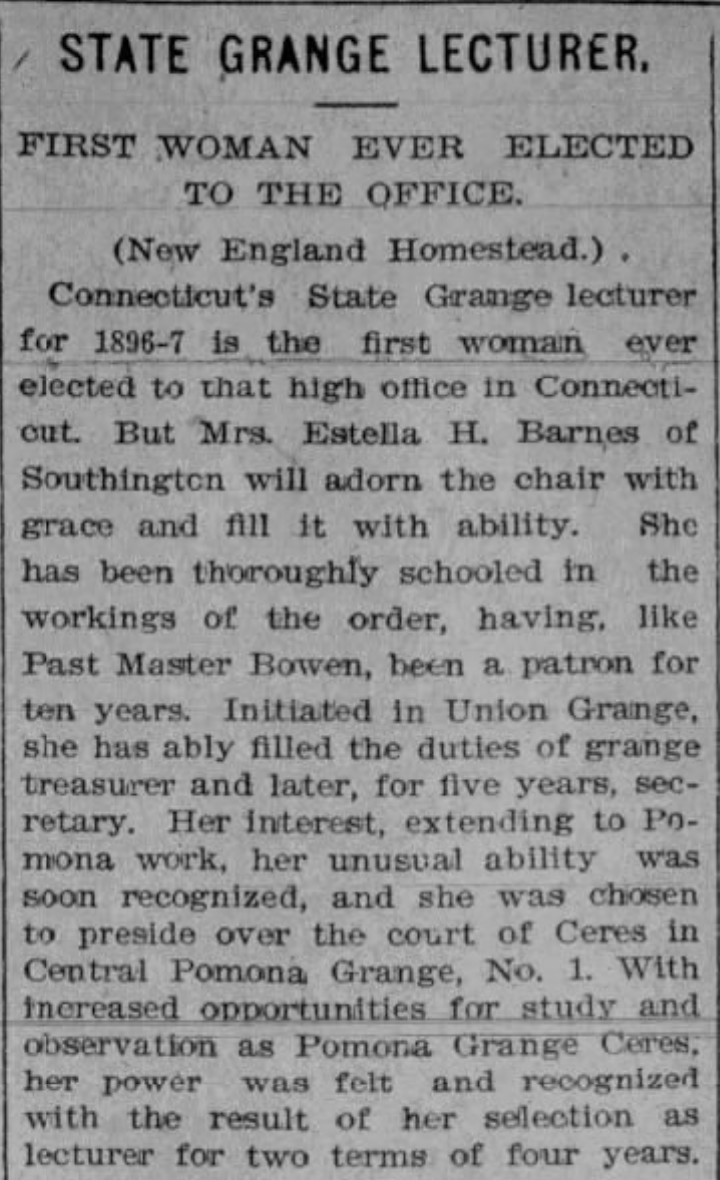

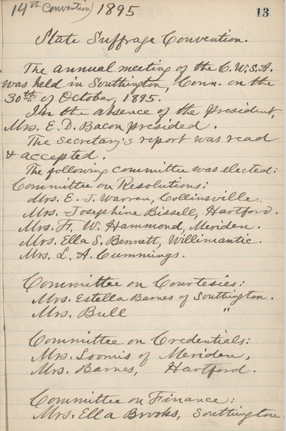

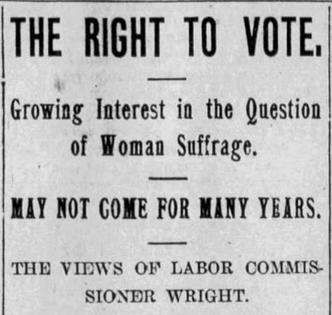

Unveiling the Legacy of Estella H. Barnes: A Champion for Women's Suffrage and Community Leader3/26/2024 By: Christina Volpe, Curator  Within the historical tapestry of Southington, Estella H. Barnes shines as a pivotal figure in advancing women's rights and societal equity. Her story is one of remarkable resilience, passionate activism, and a deep-rooted commitment to her community. Estella's legacy is particularly notable in her contributions to education, the women's suffrage movement, and agricultural reform. Her achievements are especially significant considering the societal constraints faced by women during her era. Born Lucy Estella Hills on January 30, 1847, in Albion, Erie County, Pennsylvania, Estella's life was marked by the early loss of her mother at the age of six. This led her to live in the care of her grandmother in Southington, Connecticut, where her path would eventually cross with John James Barnes (1834-1905). John was known affectionately as "Honest John Barnes" for his integrity and was deeply rooted in one of Southington's oldest families. He diligently managed an expansive farm and orchards and remained committed to civic engagement in local affairs. John actively participated in the beautification of the town's central park, known today as the Southington Town Green, in the late 1870s; John was fixing up the Congregational Church property and began filling in the ditch within the town park, planting elm trees on the south end. Unfortunately, the elms that once prominently and beautifully covered the Town Green suffered from blight and died in the 1930s.  Left: Excerpt from the minutes of the 1895 Connecticut Women's Suffrage Convention held in Southington. Below: Exception from the minutes of the 1895 Connecticut Women's Suffrage Convention in Southington. Images accessed via the CT State Library via the Connecticyt Digital Archvies.  Estella and John married on September 10, 1867. She was twenty, and he was 33. On the back of Estella and John's Intention of Marriage, her adopted father, John Phinney, wrote: I hereby give my consent to the marriage of my daughter Estella to John J. Barnes. Four children survived her: Wilfred Barnes of Torrington, Albert Barnes of Waterbury, and Dana and Addie Barnes, living with their mother when she passed. Estella's influence extended far beyond the walls of the home she built with James. In the 1890s, she actively developed Southington's suffrage efforts. The twenty-sixth annual Women's Suffrage Convention was held in Southington's Town Hall and attended by many delegates, with members from each local level organization in attendance. Photographs of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony tied together by a bit of yellow ribbon were passed out as souvenirs. Estella was head of the courtesies committee and gave the welcome address at the convention in late October 1895. Early women's rights movements in the 19th encompassed many issues beyond suffrage, including education access and expansion. Recognizing that education was essential for women's empowerment and societal advancement, activists advocated for establishing grammar schools and kindergartens accessible to all children, regardless of gender. Kindergartens, pioneered by German educator Friedrich Froebel in the early 19th century, emerged as spaces where young children, including girls, could engage in structured play and early learning experiences, laying the foundation for their intellectual and social development. The establishment of grammar schools provided formal education pathways for girls beyond basic literacy, offering instruction in subjects traditionally reserved for boys, such as mathematics and science. The Equal Rights Club of Southington met in 1895 and 1896 to discuss such matters hosted several times at the Barnes home on South Main Street. Estella emerged as a female suffrage trailblazer, becoming the first woman elected as a lecturer of the State Grange in February 1896. The Connecticut State Grange is a local organization within the larger National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, a fraternal organization founded in the United States in 1867 to promote the interests of rural communities and agriculture. The Connecticut State Grange provides support, resources, and advocacy for its member Granges, which are community-based chapters typically located in rural areas that very much included Southington at the time. These local ranges often engage in agricultural education, community service, and social events.

At the same time, Estella ran a large house with all her children. The 1890 census showed three boarders living with the family: two farmhands and one schoolteacher. In 1898, John James suffered from a paralytic shock. Estella took care of him at home for a few years, but his condition declined. The year 1905 proved to be the hardest. Estella lost her sister that summer, a grandchild, and ultimately her husband, John, on January 28, 1905; about six weeks later, she died in her Main Street home in Southington of pneumonia after a short illness. Beyond her activism, Estella was a custodian of history, delving into genealogy books and actively involved in the annual Barnes family reunion. Her intellectual curiosity knew no bounds, and she engaged in scholarly pursuits with zeal and passion. Estella's home was a sanctuary for learning and growth, where her children flourished under her guidance.

In reflection, the life of Estella H. Barnes serves as a testament to her resilience, compassion, and unwavering commitment to Southington, a place that defined her character. As we bid farewell to this remarkable woman, let us carry forward her spirit of curiosity, compassion, and dedication to a future where equality, opportunity, and justice flourish for all.  There are many love stories that have played out in both the Bradley and Barnes families. Out of all of the love stories, Alice Bradley and Norman Barnes have the most intriguing one. What started out as a forbidden courtship, eventually turned into an enduring love. Alice Bradley was born on October 22, 1849 to Amon Bradley and Sylvia Barnes. She had an older brother named Franklin and a little sister named Emma. She grew up in what is now known as the Barnes Museum. The Bradley family was one of the most wealthy and influential families in town. Amon had his hand in many of the manufacturing industries in town as well as real estate. His wife Sylvia came from a wealthy family.

“Mother made loaf cake and doughnuts. Norman Barnes took dinner with us.” – February 7, 1862 from the diary of Alice Bradley Barnes. The earliest letters we have of Norman and Alice start in 1863. While they were friends at the time, it appeared that there was an undercurrent of romantic feelings. In their letters they spoke about their everyday lives as well as expressed how much they missed each other. Norman to Alice – October 12, 1863 “…here I am all alone and I must confess that I am a little homesick. How I would like at this moment to step into your place and see you, but cannot.” Alice to Norman – October 26, 1863 “Thanksgiving is coming and I am really glad, for I suppose you are coming home then. It seems as though I had not seen you in a long, long time. We miss you very much, particularly myself as I have no one like you to play with at the table then.”

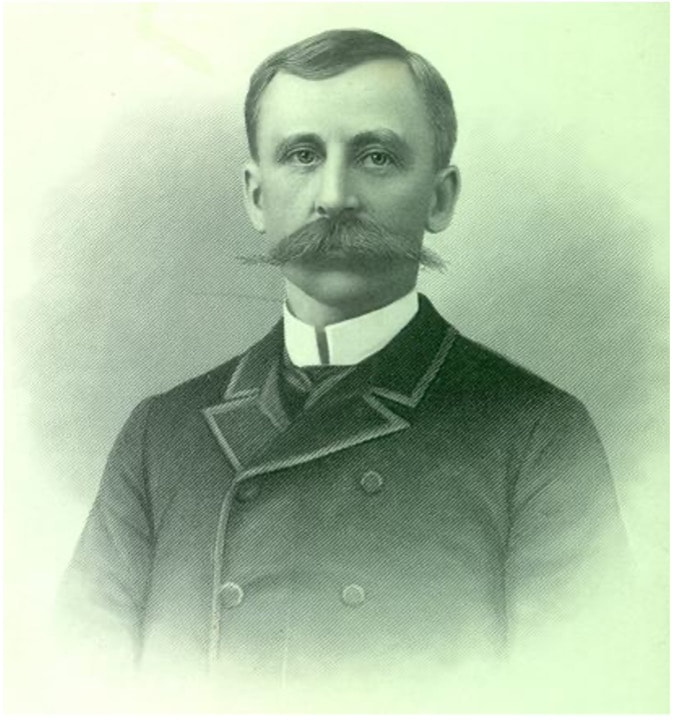

Excerpt from the letter of Norman Barnes to Amon and Sylvia Bradley. "But this I am bound to do until forbidden by Father or Mother. Allie and myself have talked of these things often. She is fully convinced that I love her with my whole heart, I am convinced that she loves me with her whole heart. Whence we ask in all earnestness that we may consider ourselves as engaged to each other, as Man and Wife, or until we are joined in the holy bonds of Matrimony, when we then would feel the full force and realize the meaning of the words Companions for Life. Pray give this earnest and careful consideration; make it the subject of much thought before you answer. But we truly feel as if it should be of necessity be answered. For certainly it would be decidedly wrong for me to win more of her affection or she of mine, and then be separated forever; it would perchance ruin us both for the remainder of Life. But this we hope will not be. We trust our petition will be granted; and still we would not wish it granted if it should be the means of making a life-long distrustance on the Family, or the cause of biter enmity for the remainder of Life's journey. Although it would be hard, better hard to give each other up."  The Bradley family ended up approving of their wedding but not before Amon decided to take Norman under his wing. In order to marry Alice, Amon wanted Norman to be able to provide her with the lifestyle she has always been accustomed to. According to Alice’s diary, Norman did work as a clerk and a teacher around 1863. “My carte devisees came today. I had a dozen. Norman Barnes came to board with us today as he has commenced to be the clerk in the store. “ – April 27, 1863 – From the Diary of Alice Bradley Barnes It wasn’t until 1870 that he left behind the world of teaching permanently. His experience under Amon empowered Norman to go on to explore other business ventures including becoming sectary and treasurer of Atwater Manufacturing company for almost 30 years.

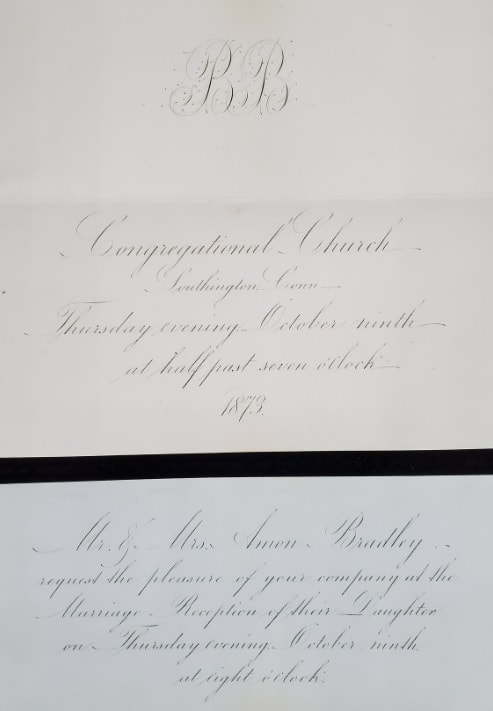

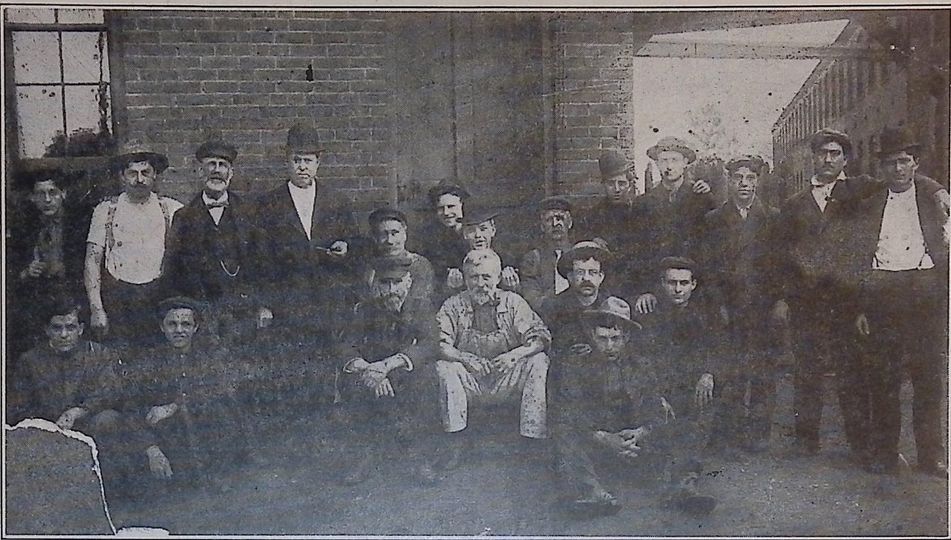

Around 1869, Norman got Alice a diamond ring. She mentions that they were getting it engraved. On Christmas eve, he gifted her the ring. “Norm gave me a very pretty little diamond ring.” – December 24, 1869 Alice and Norman got married on October 9, 1873 at the First Congregational Church in Southington, CT. They share an anniversary with Amon and Sylvia. “Today is my wedding day, and pleasant it is, and I am so thankful too. I have a great many flowers given my friends and neighbors, and a nice lot of bridal gifts, many more than I mentioned, in this book. I gave Norm a nice gold watch; he gave me an elegant pair of heavy gold chain bracelets. “ - October 9, 1873 – From the Diary of Alice Bradley Barnes. After their wedding, they went on a honeymoon to New York. They stayed at the Sturtevant House Hotel on Broadway. They saw "Fanchon the Cricket" at Booth's Theatre. They also spent time with friends and attended a fair in Brooklyn. Their honeymoon lasted five days. After marriage, Norman and Alice lived with her parents for the next 10 years. During the 19th century, it was very common to live in a multi-generational household as family was seen as the center of everything. By then Norman was accepted and became very close with the Bradley family. Even after they moved, they made it a point to visit Alice’s parents every day. Alice and Norman were both extroverts who loved going to socials and had a love of performing. Often times, Alice’s little sister Emma would tag along. Alice was one of the founders of the Clotho society which started out as a community fundraising club and eventually turned into a drama club which Norman and Alice acted in. Around 1882, Alice and Norman had a house build across the Southington town green where they moved shortly before Alice gave birth to their son Bradley on January 27, 1883. When Bradley was old enough to write a diary, he spoke of his everyday life with his parents. Every birthday, she and Norman would deposit roughly $50 into an account for Bradley. That is worth around $1600 today. When he was younger, they would bake and pick fruit together. Alice and Norman passed along their love of theater to Bradley often attending local plays and concerts at their church and town hall. According to his diary, he performed during the Christmas exercises although they were small parts. Unfortunately, Alice died 1897 after a months long respiratory illness. She was only married to Norman for 24 years and Bradley was only 14. Both Norman and Bradley were stricken with grief. Bradley’s grades slipped and Norman constantly worried about him. Norman would mention Alice in his letters to Bradley expressing how beautiful she was and how she would love the location he was visiting. He also worried that Bradley would get sick like her and would end his letters saying “don’t get sick.” Norman never remarried. Alice and Norman’s legacy lived on in their son Bradley. It was due to Bradley’s passion for preserving his families history and artifacts that we are able to tell the love story of Alice and Norman generations later. Labor Day: Honoring Struggles, Celebrating Achievements, and the Southington Cutlery Company Strike8/28/2023 Labor Day, a holiday now synonymous with barbecues and relaxation, has a rich history that dates back to the late 19th century. Its origins trace back to the labor movement's fight for fair working conditions, hours, and wages. The Barnes Museum takes you on a journey to the early days of Labor Day, providing a glimpse into the struggles and triumphs that paved the way for the holiday we celebrate today. Thanks to the Central Labor Union's visionary plans, the inaugural Labor Day holiday occurred on September 5, 1882, in New York City. A mere year later, on September 5, 1883, the Central Labor Union once again brought the nation together to celebrate the principles of labor rights and workers' dignity. During these times, the Southington Cutlery Company became a focal point of labor tensions in this area. In July 1880, the company employees initiated a strike due to a decision by the directors to deduct 10% from their pay. This was a clear demonstration of workers' collective determination to protect their rights. By 1882, the Southington Cutlery Company transitioned into making razors, experiencing a surge in production and busier times than ever. The company's dedication to evolving its products mirrored the evolving spirit of the labor movement. The year 1886 marked both expansion and strife for the company. The company represented the epitome of labor's vitality, with over a hundred men employed in their knife department, including grinders and finishers. However, in November of that year, a hundred men from the knife department went on strike in response to another 10% wage reduction. This significant strike, organized by the Knights of Labor, showcased the unity and determination of the workers. The Knights of Labor was a prominent labor organization in the 1870s. By July 1886, Connecticut boasted nearly 12,000 Knights of Labor members spread across 118 local assemblies. Among them were women textile workers in the eastern Connecticut mills, adding a dimension of gender equality to the labor movement. The influence of the Knights even extended to the state's legislative arena, with 37 Knights of Labor members in the 1885-86 legislative session. However, 1886 would be a turning point for the Knights of Labor in Connecticut. The Knights of Labor's national reputation took a hit when they were accused of being linked to the Haymarket Riot on May 4 in Chicago—an event marked by labor-related protests that turned violent, casting a shadow over the organization's standing. In Connecticut, the local assemblies encountered challenges in rallying support for members' strikes, such as those at the Derby Silver Co., the Southington Cutlery Co., and the P. & F. Corbin Co. in New Britain. Despite their efforts, these local assemblies leaned towards negotiation over confrontation with anti-union owners. This stance led to a decline in the Knights' membership in Connecticut from 12,000 to 5,622. On November 23, 1886, some striking employees of the wood screw shop at the Southington Cutlery Company began to return to work, indicating a turning point in the labor conflict. The beginning of 1887 saw further tensions as the company considered repurposing the knife shop and paused knife production until wage disputes were settled. On January 22, 1887, the strikers, led by the Knights of Labor, marched to the Southington cutlery knife shop and collected their tools, a symbolic gesture of their unity and resolve. The strike continued for twelve weeks, eventually concluding in February 1887. While some strikers grew disheartened about achieving the desired pay increase, several men agreed to return to work as a collective entity, demonstrating the strength of solidarity. The company's declaration that certain leaders would not be able to return to work there underscored the lasting impact of this labor movement.

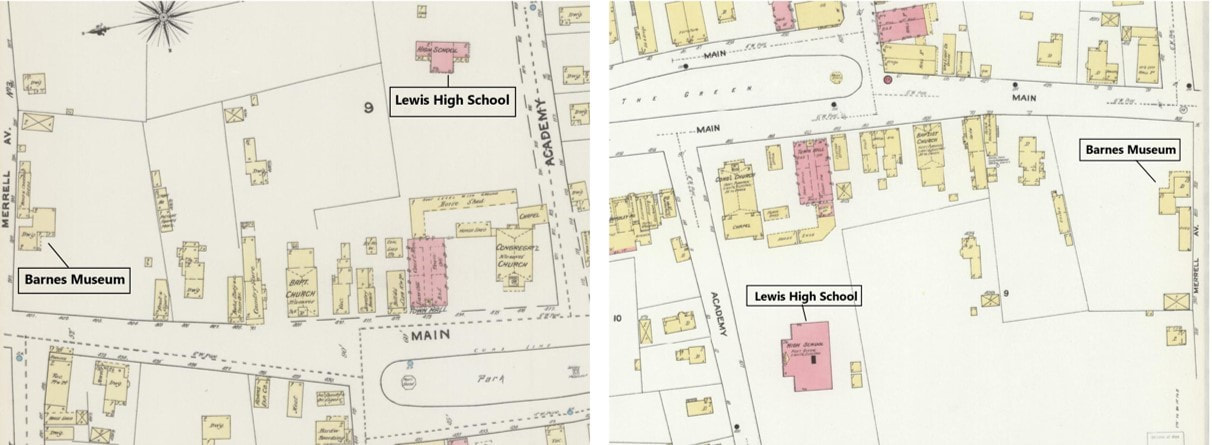

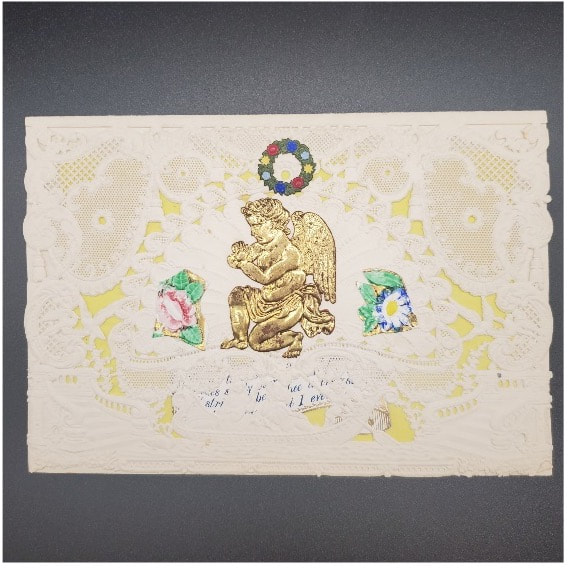

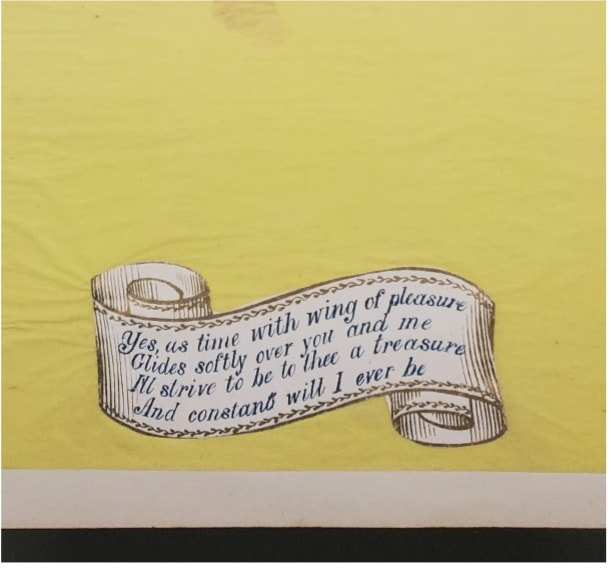

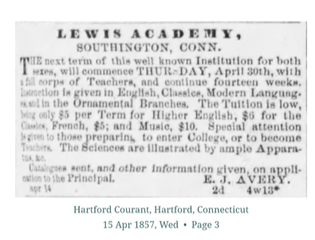

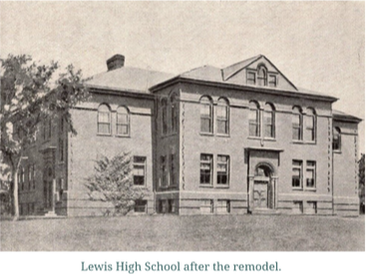

As we bask in the joy of Labor Day, let's not forget the resilience of those who came before us, the champions of workers' rights who navigated through challenging times to lay the foundation for the dignified workplace we enjoy today. The Southington Cutlery Company's labor struggles are a testament to the enduring spirit of unity we commemorate on this special day. "A school for the instruction of youth in the Latin and Greek languages, mathematics, geography, and the other branches of science higher than are taught in the common schools." - From the will of Sally Lewis  The Founders Lewis Academy was founded by Sally Lewis and her cousin Addin Lewis of Southington, CT. Sally Lewis was born to Job Lewis and Hannah Curtiss. While her exact birthdate is unknown, she was baptized on February 14, 1773. Her father was a shoemaker and tanner. Her family was also wealthy. Since she was the only sibling that wasn't married, her father left his house to her. Once she settled into the home, she wished to be more involved in the community of Southington. Although wealthy, she was also a woman and was given the cold shoulder by the men in town. Sally was always passionate about education. In 1828, she taught women basic education skills in a room at the First Congregational Church. While women's opinions were often disregarded in Southington, some men were considered outcasts. One of these gentlemen was named Jesse Olney. Jesse was a school teacher ambitious about bringing a higher quality education to Southington, CT. He wanted Southington to be the model for education in hopes that more towns would follow suit. However, the men in town never took it seriously. That didn't stop Jesse. In 1829, he approached Sally Lewis due to her wealth, hoping she would fund a new school. She would listen as Jesse shared his ideas but never shared hers. Jesse all but gave up until Sally died in 1840. In her will, she left $3,579.62 of her estate to go toward a school for higher education. Although Sally didn't voice her thoughts about a school openly until her death, she did confide in her cousin, Addin Lewis. Addin was born in 1780 to Nathaniel Lewis and Sarah Gridley. He moved to Alabama at a young age and became the mayor later in life. He would often write to Sally, and they would talk about a possible school that could be built in Southington, CT. Sally's influence inspired Addin to leave about $15,000 of his estate to go toward Lewis Academy when he died in 1842. $5,000 was allotted to build the school, and the rest went towards paying teachers and "necessary expenses."  The Opening of Lewis Academy Addin Lewis's contribution to the new academy was not without its stipulations. Although education was previously taught inside a church, he did not want this new school to be influenced by any religion. The school was not allowed to take faith into account when admitting students. However, there must be a maximum of five trustees of the school, and they must be a member of the First Congregational or First Baptist societies. The first trustees were Romeo Lowry, Julius S. Barnes, Lucas Upson, Alfred Hotchkiss, and A. Perrin Plant. In 1843, "Lewis Academy," was located in a lecture room in the "Old Chapel." However, it was not named Lewis Academy until September 21, 1846, during a trustee vote. The "Old Chapel" was located where the town hall is today. Henry D. Smith was the first principal of the school. In 1846, the board planned a new building dedicated to Lewis Academy behind the First Congregational Church on Academy Hill. On September 14, 1846, the building committee was elected. The members were Amon Bradley, Captain Levi Upson, A. Perrin Plant, and S. S. Woodruff. They contracted Captain Samuel Woodruff to design and oversee the new building. Woodruff was a local contractor who built both public and private buildings. On December 4, 1848, the new and permanent building of Lewis Academy opened its doors. "The institution is located in a town healthy, central, easy of access, and widely known for the interest taken in the subject of education and for the excellence of it's schools. The building is large and elegant, finely situated, and fitted up in the best style of modern improvements in school architecture." – Southington News, Southington, CT, August 15 1857, pg. 13 *Note that Lewis Academy became Lewis High School in 1882. The location was still the same. (Left Image) 1890 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map with the site of Lewis High School - (Right Image) 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map with Lewis High School's location after being remodeled. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.  The first principal for the new academy was Elias B. Hillard. He also taught the students alongside teachers E.D. Morris, N.S. Monross, and S. Fenn. Students from all over the state attended. Their families had to pay tuition that would vary each term. Tuition was the following... $5.00 for English Studies $6.00 for higher branches of Education $7.00 for languages such as Latin and Greek $10.00 for musical instruction The families of the students would also have to pay for textbooks. Addin Lewis stipulated that ten Wolcott students were eligible for free tuition per semester. The school was open all year and divided into three terms. The first term started on 10/30 and was 15 weeks long. The second term began on 2/12 and also lasted 15 weeks. The last term started on 6/11 and was only 14 weeks long. Students would have roughly three weeks to one month off in between terms. The main academic goal of Lewis Academy was to teach both men and women how to think critically, investigate issues, and become well-rounded people that would carry them throughout their lives. Students received a classics education that included mathematics, geography, English, science, music, etc. Lewis Academy would be today's equivalent of a college preparatory school.  The End of the Academy In 1882, Lewis Academy became a free public school and was renamed Lewis High School. There was no longer an admission process, and all Southington students were welcome. As a result, the building was remodeled in 1896 to accommodate the influx of new students. In 1950, Southington decided to build a new high school which is now Southington High School. Lewis High School was then converted into Lincoln Lewis Middle School in 1952, which taught 6th and 7th graders. The building was eventually razed in 1967 when it was no longer used as a middle school. Remodeling the building to be used for other purposes proved to be too costly. On November 29, 1884, H.D. Smith and Stephen Walkley formed the Sally Lewis Academy Association. The first meeting took place in a conference room at the First Congregational Church. Membership was contingent upon being an alumnus of Lewis Academy or a direct descendent or spouse of a student who attended Lewis Academy. Their annual meetings consisted of two parts. The first would be a business meeting with guest speakers. Members would talk about the happenings at Lewis High School and read letters from previous academy alums. There was a luncheon before the second part, which was a reunion. They also held special events, such as a ceremony to unveil a bronze plaque in honor of Sally Lewis In 1903. It was located at Lewis High School. The association had a ceremony in 1905 to unveil a portrait of Addin Lewis that was painted by Samuel Morse, who invented the telegraph. The Sally Lewis Association disbanded on June 28, 1933, after the last living alums died. Artifacts from the Academy September 22, 1858 – I began to go to school for the first time to the academy. My teacher's name was Mr. Frost" – From the diary of Alice Bradley Barnes. The children of the most prominent families in Southington attended Lewis Academy. This included Franklin, Alice, and Emma Bradley, who were the children of Amon Bradley. All of the artifacts pictured are in the Barnes Museum collection, the homestead of Amon Bradley. Written by Nadia D. Before Hallmark! The origins of the commercialization of Valentine’s Day cards in the Victorian Era2/14/2023  It has been said over the years that Valentine's Day is a "Hallmark Holiday" due to the myth that it was invented to sell greeting cards. However, Valentine's Day doesn't have commercial or even romantic origins. Everything from the roots to Valentine's Day's commercialization is a tale. We need to go back to the beginning as we unwind this tale. What are the origins of Valentine's Day? The holiday was believed to be inspired by a pagan festival called Lupercalia that dates back as far back as the Roman Empire. The festival celebrated fertility on February 15th. It may seem romantic, but the festival was a bit morbid. A goat and a dog would be sacrificed in the same cave where the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus were believed to be born. The men would then run naked around the city, slapping women with the hides of these animals. This part of the ritual was said to promote fertility for a year. Then there was a matchmaking lottery system that would pair couples together for a year.  They tried to end this celebration as Christianity and Catholicism started gaining political power. When Pope Gelasius came to power, he invented a new holiday to celebrate St. Valentine on February 14th and replace Lupercalia. However, there are twelve St. Valentines throughout the history of the Catholic Church, and it is unclear which one the holiday is named after. There are two possible candidates: St. Valentine of Rome and St. Valentine of Terni. Unfortunately, the evidence is blurry. Both candidates are martyrs. St. Valentine of Rome was jailed for giving aid to other persecuted Christians. He befriended his jailor's daughter after healing her of her blindness. The last letter he wrote to her ended with "your Valentine." When marriage was outlawed for soldiers, St. Valentine of Terni would secretly marry couples. He was also executed for it. Another theory is that the two St. Valentines were the same person. Geoffrey Chaucer (1349 – 1400) was the poet who was the first person to associate Valentine's Day with romantic love. He wrote a poem called "Parliament of Foules," about a bird choosing its mate from multiple suitors. Out of the almost 700 lines in the poem, one sentence references Valentine's Day. The passage reads, "For this was on St. Valentine's Day when every bride cometh there to choose his mate." This poem talks about choosing a love match during a period when political alliances through marriage were common among the aristocracy. The first Valentine's Day card was believed to be sent by Charles, the Duke of Orleans, in 1415. He wrote a Valentine's Day poem to his wife from his jail cell while he was a prisoner of war in the Tower of London after the Battle of Agincourt. The first few lines read, "Je suis desja d'amour tanne, Ma tres doulce Valentinée." (I am already sick of love, My very gentle Valentine). It was a very melancholy message due to his circumstances. Tragically, his wife passed away before he was released from prison. Sending sweet letters to a loved one on Valentine's Day became more common. By the late 18th century, Europeans began to decorate these letters with lace, embossing, and illustrations creating this three-dimensional effect. Around this time, England began to print commercial Valentines by machine. The customer can then take those Valentines and choose verses to suit their situation. Some even added more embellishments to their handcrafted Valentines. Who manufactured the first Valentine's Day Cards? Regarding mass-producing Valentines, two conflicting yet intersecting stories originate in Grafton and Worcester, MA. Since there is little historical evidence about who mass-produced Valentine's Day Cards first, we can only guess based on each account. The ambiguity stems from the book "A History of Valentines" by Ruth Webb Lee. In her 1952 book, she solely credits Esther Howland as the person who first mass-produced Valentines.  Esther Howland was known as the "Mother of American Valentines." She was born in 1828 in Worcester, MA, to her parents, Southworth and Esther Howland. In 1847, she graduated from Mount Holyoke College and was an aspiring entrepreneur. She received a beautiful English Valentine during the same year and was instantly fascinated by it. She devised an idea to form a business to sell these types of Valentines in America. Her father owned an S.A. Howland & Sons store that sold books and stationery. Esther asked him for supplies such as thick paper, lace, illustrations, etc., to make a few prototype Valentine's Day cards. She created these three-dimensional cards using lace, embossed envelopes, and pictures to make a collage. Inside, she would paste a small piece of paper with a four-line verse as the message. She gave her brother about a dozen prototype Valentines and then convinced him to try to sell the Valentines during his business travels around Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire. She thought she would only get a total of between $100 and $200 orders. Her brother brought back $5,000 worth of orders to her surprise. Her new business was an instant success, and she decided to expand. She took over the third floor of her home and started off hiring four ladies who recently graduated with her. She was said to pay her employees well above average. They started an assembly line to mass produce English-inspired Valentines. Each woman would have a specific section to work on and then pass it to the next lady to add another section. In the end, there was a complete Valentine which would be around 75 cents each. Some of her more intricate cards cost about $35 during that time. When Esther sold off her business in 1881, she made $100,000 per year. That equates to just under $3,000,000 today! While Esther is almost solely credited with starting the first company that mass-produced Valentines, there is a different account. In 1809, Jotham Taft was born in Grafton, Ma. Like Southworth Howland, he also sold stationery. He and his wife vacationed in Germany in 1839 and brought back Valentine's cards. Taft started mass-producing Valentine's Day cards around 1840 through the New England Village Company. He is known as the "Father of American Valentines."

What is interesting is the fact that Esther and Jotham knew each other. Both of their families were friends and he may have been the one to mail her the English Valentine back in 1847. He is also believed to have been her mentor and taught her how to make Valentines. Jotham's son Edward went into business with Esther Howland in 1879. Together they formed the New England Valentine Company. Meanwhile, in Worcester, Sumner Whitney and his wife opened a stationery store in 1858 and sold their Valentine's Day cards. When Sumner died in 1861, his younger brothers Edward and George Whitney took over the business. They named it "Whitney Valentine Company. It is believed that George worked for Esther Howland, making Valentines before then. If it wasn't for their maker's stamps, Esther Howland and George Whitney's Valentine's cards would be indistinguishable.  Edward left Whitney Valentine Company in 1868. Now the sole owner, George continued a highly successful business and decided to expand. In 1881, he bought out 10 Valentine's card companies, including New England Valentine Company. He now sold Victorian Valentines and cards for holidays such as Christmas and New Year's. His Valentine's Day cards slowly evolved into what we see as modern-day greeting cards. Valentine's cards were now made using machinery rather than an assembly line. It was now more cost-effective to forgo the intricate 3-D effect of Victorian Valentines. Upon his death in 1915, his son Warren took over the company. Whitney's son, also named George," eventually took over until the company's demise during WWII. Unfortunately, with paper shortages and the rise of other greeting card businesses, Whitney Valentine Company could no longer sustain itself and liquidated. The business of greeting cards is still thriving today, with aisles of cards displayed at the local grocery store. With today's technology, greeting cards can even be sent by email. The craft of mass-produced handmade greeting cards may no longer exist, but the sentiment is the same. These Valentine's day cards are a gift to let someone know you are thinking of them.

By: Nadia Dillon, Outreach Coordinator & Preservationist at The Barnes Museum By: Nadia Dillon The tradition of putting up and decorating Christmas trees dates back to the 16th century in Germany. Trees were originally decorated with lighted candles, fruit, and nuts. This slowly began to change in 1846 when a gentleman named Hans Griener began to make glass ornaments at a Glassworks Factory in Lauscha, Germany. He is a descendant of a gentleman also named Hans Griener who opened up the glassworks factory back in 1597. The original glass ornaments were shaped to look like fruits and nuts. The ornaments were made by using blown glass and putting it into a mold. The inside of the ornaments had mercury and tin in them to make them shine. When the dangers of mercury became known, sugar water, and silver replaced it. The outside of the ornament was painstakingly hand-painted and decorated ornately.

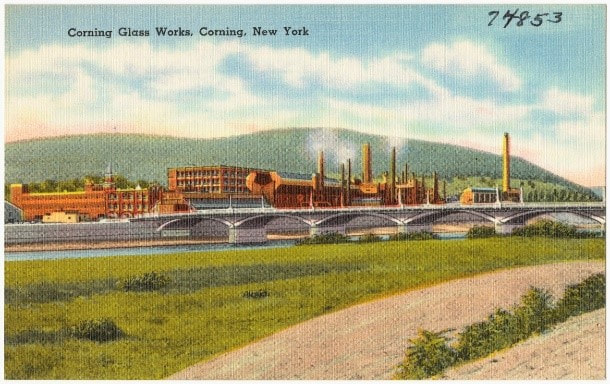

Before the war, Max Eckhardt used to import Christmas ornaments to the US to sell them. Anticipating the imminent shortage of glass, Eckhardt created a company called Shiny Bright that would sell US-made glass ornaments. He, along with Bill Thompson who was a representative of Woolworth’s Department store, negotiated with Corning Glass Works in New York to mass produce the glass ornaments. Before making ornaments, Corning Glass Works manufactured lightbulbs. In 1939, Corning Glassworks began to experiment with making glass ornament “blanks” that used the same machines that made lightbulbs. The ornaments were made by pouring hot glass in molds on a conveyer belt. Puffs of air would then be blown into the glass to create its shape and hollow interior. When continuing along the conveyer belt, the ornaments would then get a silver coating inside to give them their signature shine. Corning Glass Works ended up adding 500 jobs to the factory and producing over 40 million US-made glass ornament “blanks.” Shiny Brite would then go on to paint and decorate the ornaments and distribute them to stores all over the United States. In 1939, F.W. Woolworth ended up purchasing 200,000 glass ornaments to sell at their store. Many stores around the United States began to follow and Shiny Brite ornaments were now sold nationwide Advertisement GalleryShiny Brite ornaments were simple and a stark deviation from the ornate German glass ornaments. Shiny Brite ornaments came in many colors including pink, blue, red, and green. A common design with the ornaments was thick stripes that would come in many colors. Due to the shortage of metal, some of the ornaments had cardboard tops. The ornaments were mostly round but there were some oblong shapes also. Due to the ban on silver nitrate, Corning Glass Works could no longer put a silver coating inside the ornaments. To make up for this, tinsel was added inside some of the glass ornaments to capture the shine. Ornaments were either sold individually or in box sets. Each ornament was sold for as little as 10 cents which would be approximately between $1.50 to $2.00 today. The boxes carried sets of between 6 and 12 ornaments. Each box boasted that the ornaments were American-made. Many boxes even had a photo of Santa Clause shaking hands with Uncle Sam. Ornament Photo GalleryConsumers grew to love Shiny Brite ornaments due to their simplicity, low cost, and being made in America. They could no longer justify importing the more ornate and expensive glass ornaments from Germany. Shiny Brite ornaments were still popular in the 50s and 60s and carry nostalgia for much of the baby boomer generation. By the 70s, the production of Shiny Brite ornaments stopped, and are now a collector’s item that we are very lucky to have on display this Holiday season.

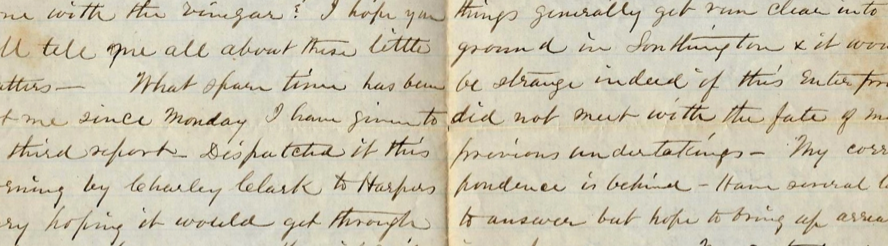

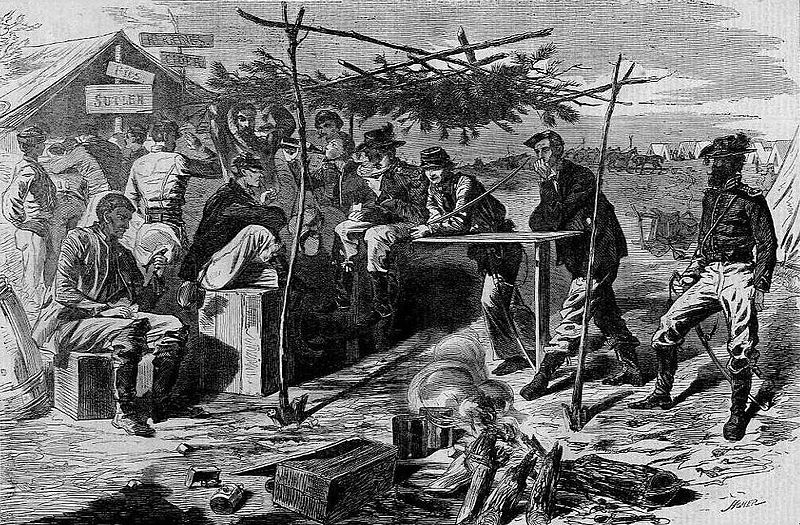

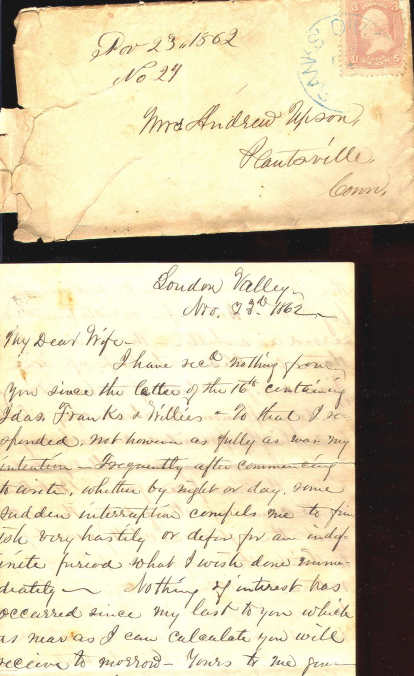

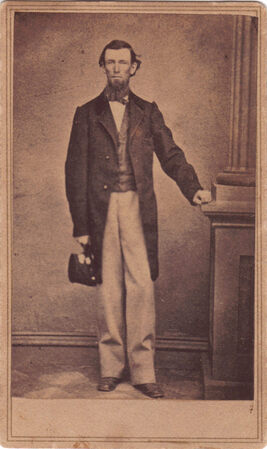

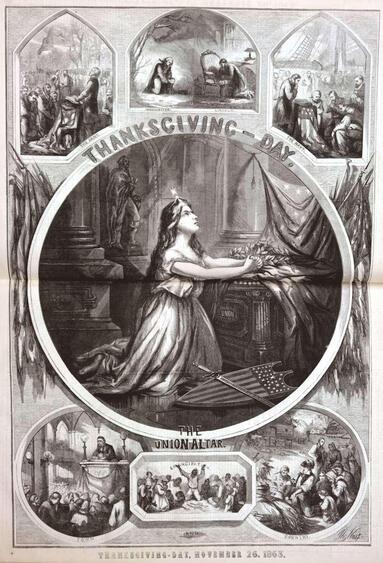

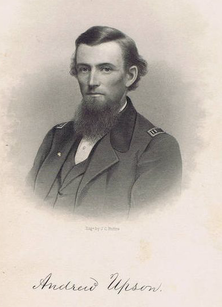

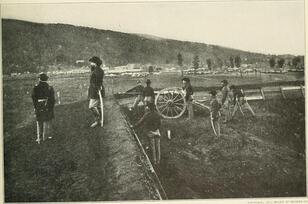

By: Christina Volpe, curator of The Barnes Museum  Andrew Upson was born in Southington, Connecticut on May 18, 1825. He graduated from Yale College in 1849 (It became Yale University in 1887). On April 15, 1850, he married Elizabeth Gridley. The Upson family ran a successful farm in the Plantsville area in Southington. Elizabeth and Andrew had four children: Ida Maria, Francis Root, William Calkins, and Mary Brooks. On July 21, 1862, Upson enlisted as a 1st Lieutenant in Company E of the 20th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. He died on February 19, 1864, in Tracy City, Tennessee. While he was away from home, he wrote his family and friends often, accounting for daily life as a Union soldier and his unique perspective of daily happenings during the Civil War. Winslow Homer's 1862 wood engraving titled Thanksgiving In Camp Historically, 1862 was the last year that Thanksgiving was celebrated on varying dates in the Northern states. To promote cultural unity between the North and South, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed that the Thanksgiving of 1863 would be held on the last Thursday of every November. The Northern states celebrated their first federally recognized Thanksgiving in 1863, while the Southern states observed the federal holiday only in the years following the Civil War. Thanksgiving blessings from Captain Andrew Upson to his wife. November 23, 1862 “I hope you will make thanksgiving with usual ceremony & enjoy with more fullness than ever before – Just see how much we have for which to offer up devout praise – First our little circle unbroken & capable of participating in the Anniversary – Second our health – We have been sick & recovered – Thousands have died young & old have been taken we are alive – How strange that seems! Our four children all spared – all well – Third our numberless blessings – I left a full barn & more crops to be gathered – You all have enough to eat, to wear – You have quiet & may hope for its continuance – Could you see the people where war makes its track. I am sure you would praise & thank God for your own condition. Lastly, thank God that you & I & we all are able to do something for the country He has so bountifully blessed – thank Him that in this sore trial we have hearts willing to meet privations & even sacrifice life under his command if so be liberty & good government may be upheld & great blessings flow down to our posterity – Be think you at the pristine board & all the day how often We have together enjoyed a Thanksgiving because Patriots lived years ago – recall their heroism – their great suffering & count as light indeed what this crisis demands of us. Is it an honor now to be patriotic?” Captain Andrew Upson's 1862 Cabinet Card The following year President Abraham Lincoln made a proclamation declaring the last Thursday in November be observed as Thanksgiving. Another attempt at unifying a mourning nation - whose losses at the battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863 had surpassed 50,000 lives. "I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, …to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving... And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him …, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union." Thomas Nast 1863  With the war still carrying on, Captain Upson wrote a Thanksgiving blessing to his family once again. Reporting from Fort Harker near Stevenson, Alabama (pictured right) the Captain had been stationed there for some time and wrote home to his wife often. Fort Harker was vital during the campaign against the confederate General Braxton Bragg in Chattanooga Tennessee in July of 1863 and the small town of Stevenson also served as a refugee camp and hospital following the battle. Occupation of the rail town ensured that the Union had control of supply lines in southeastern Tennessee and northeastern Alabama. In other letters that we will not be sampling here today – Captain Upson described seeing the refugees and their small children. He describes seeing former enslaved African Americans eager to fight with the Union. Several of the sentiments he has developed from being around and in the camp are conveyed to his children in the letter below. November 18, 1863 Stevenson, Alabama To Ida, Frank, Willie & Mary My Dear Children, I suppose this letter will arrive at its destination about Thanksgiving Day – Hoping it may add to your happiness on that occasion I sit up a few moments although it is time to go to bed and everyone around is asleep – Perhaps, children you do not understanding the real meaning of Thanksgiving Day – In the 1st place, you have enough to eat – that is, God has made the grain and fruits to grow during the past season, and so you have food – If now, there had been a scarcity of rain, or if war had prevailed around your home the crops would have failed – Down here there are many sections in which the corn was cut off for want of showers – In other sections it was all destroyed by the army – The people have scarcely nothing to eat – Papa has seen numbers of these people – Men, women and children – They had none of those good things that contribute to your comfort and for which you should give thanks to God – In the 2d place, you have a snug and quiet home – In this part of the country families are often driven from their houses – They have to leave nearly everything and flee away to strange places – Often times women and their little ones are compelled to walk day and night – If the weather is cold or wet they suffer much and frequently become sick – You are not disturbed in this way and there is a reason why you should thank God who rules over all things – In the 3d place you have books, papers, schools and various privileges which thousands of children in other parts of the country know nothing about – It is a bad thing to grow up in ignorance – it is a bad thing to live where the people do not go to meeting or have good books and maps and the means of acquiring knowledge – God has case your lot where you have the benefit of almost every advantage to become learned and wise and useful – I hope you will so far understand this as to be thankful for your opportunities and not neglect them – Now, my children, Thanksgiving Day is appointed that we may call to mind how much we owe to the Great and Good God – We are very apt to think too little of our common blessings – But if they are taken from us we begin to see their value – I hope you may never lose your schools, or your home, or the chance of enough to eat…I should like very much, Dear Children, to sit down with you at the Thanksgiving Supper – Perhaps another year God will permit us to meet on this anniversary – Whatever may be our condition let us be very thankful – Papa sends his best wishes and his tender affection to each of you and also to Mother and Grandmother – From your loving father, Andrew Upson Unfortunately, Captain Upson would not be so blessed as to make it to the next Thanksgiving Supper with his family. Less than two months after he wrote this letter he died after succumbing to two gunshot wounds sustained during an ambush by Confederate soldiers on Tracy, City Tennessee. Captain Upson was there with Company B of Connecticut’s 20th Regiment to defend the rail line in Tracy City. The captain had been by the train depot with ten of his men when the ambush occurred. He was shot and captured with his men and after four hours was released. During his time recovering in the days following the incident Captain Upson continued to write home to his family. Word of mouth and local reporting indicated the Captain was feeling better. Several days later he died and on February 29, 1864, his body returned to Southington for burial and is interred within Quinnipiac Cemetery.

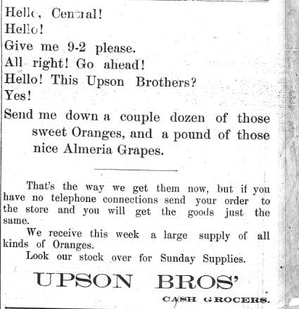

The Barnes Museum has the honor of housing the Captain Andrew Upson Civil War Letters and Diaries within the archival collection. The collection is open for scholarly research and select items belonging to Captain Upson remain on display. To learn more about him or his grand daughter Leila Upson Barnes's legacy contact us today! By: Nadia Dillon The Upson Brothers

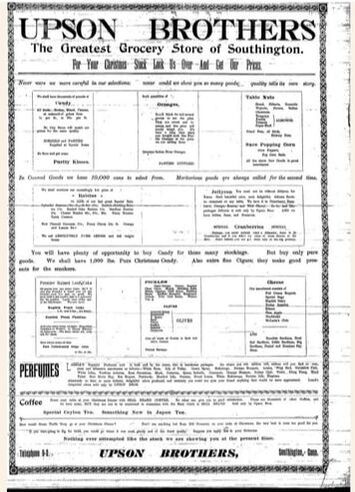

Upson Bro's Grocery Store In 1884, Frank R. Upson and William C. Upson opened the firm Upson Bros where they were partners. They opened Upson Brothers dry good store on 15 Center Street in Southington. Unfortunately there was also a fire that originated in the store on in January of 1885. Their entire stock was lost. The fire spread to the other stores in the building accumulating approximately $18,000 in losses. With inflation, today that number would equate to around $612,000. The Upson Bro's alone had $7,000 in loses which would be around $238,000 today. One firefighter was injured. Luckily the building still remained and the brothers were eventually able to replenish their stock. Frank used to go to New York city about once a month to buy new stock.

Southington's Irish Domestic Servants: Hannah Deady and Sarah Deegan on the Bradley Homestead3/17/2022 Millions of Irish immigrants came to America in the nineteenth century seeking reprieve from centuries of economic and political turmoil in their homeland. These immigrants grew their families and businesses while contributing and assimilating to a changing American industrial economy that was not always welcoming. Irish immigrants were amongst the first to come to America working as domestic servants, seeking financial success in factories, and building local businesses; many following the same settlement patterns that the Yankee settlers before them had taken. By 1840 there were more than seventy-eight thousand Irish immigrants in America and by 1850 this number rose to be more than ninety thousand. Connecticut’s first Irish-supported newspaper the Catholic Press began production in 1829. It is here that we learn about one of Southington’s earliest Irish American residents: Peter Dayle died August 7, 1829; the Catholic Press was used at the time to communicate deaths, arrivals, and post missing person descriptions to reunite families separated during their travels. Letting readers know that he passed was the best chance for someone to know how and where he passed away. In the archives of Connecticut’s church records, Peter’s death is noted as drowning, and next to his name he is referred to as a “foreigner”. While it is unclear how or why Peter found himself in Southington in 1829 – it is likely Peter and his family were fleeing persecution from the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Irish Catholics were persecuted during this time and young Peter would have only been thirteen years old. Southington’s Irish American community is tied to The Barnes Museum in several ways. Living on the Amon Bradley homestead in the 1860 Census was an Irish woman named Hannah Deady (1827-1888), then age 35, and working as a servant in the household. In 1860 Amon Bradley was 48 and employed as a merchant with a personal estate value of $30,000. Also listed living on the homestead in 1860 were Amon’s wife Sylvia age 42, and their children Franklin age 17, Alice age 10, Emma age 2, and cousin Henry R. Bradley, a local attorney practicing in the town of Southington. Eldest daughter Alice writes in her diaries about Hannah and some of the duties she carried out during her time working on the homestead; these included preparing cider or jam with the family, cleaning rooms, and occasionally going to clean houses owned and rented out by Amon Bradley. The article pictured names brothers William and John Deady as bearers at her funeral. A twenty-year-old William Deady arrived in America on May 27, 1850, on the ship Atlas at New York harbor. Traveling with him was his younger nineteen-year-old brother John Deady their older sister Hannah, then age twenty-three. William and John worked, lived, and raised their families in Southington throughout the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. John Deady was for a time highly respected as “baggage master at the Southington Depot”. William worked for Peck, Stow & Wilcox not too far from his home on Bristol Street where he and his wife Mary McCall raised their six children, their youngest son named John after his uncle John. Pictured is the Irish-American Donahue family of Southington. Photo is from the collection of the Connecticut Historical Society. Irish families throughout the country and in Southington formed tight-knit communities. The Bristol Street area alone where William Deady’s family lived according to the 1880 Census listed countless Irish surnames. This makes much sense as the first Irish Catholic church in Southington was St. Thomas located still today on Bristol Street. As early as 1852 Irish Catholic services were being provided for Southington residents out of Meriden. Seeking to establish a church in Southington as an extension of St. Rose’s Church in Meriden, Bishop Francis P. MacFarland purchased the tract of land on Bristol Street in 1859. On July 4, 1860, the cornerstone of St. Thomas was laid with some 500 local Irish Catholic residents ready to attend services. When Hannah Deady died on March 9, 1892, she was interred in St. Thomas cemetery. Alice Bradley’s diaries reveal that throughout the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s the family’s hiring preference for house labor assistance were Irish American women. Though the 1870 census does not list any servants as working in the household Alice’s diary mentions a girl named Maggie Daly coming to work with the family in 1871. On the 1880 Census, the Amon Bradley homestead (future home to The Barnes Museum) lists Sarah Deegan then age 17, as living and working for the household as a servant. Sarah Deegan was the daughter of Edward and Sarah Deegan, Irish natives that migrated to America in 1855 at the ages of 17 and 18 respectively. On the 1860 Census, the growing Deegan family is living in Southington with Edward working as a machinist. Ten years later in 1870, Edward and Sarah list five children living in the household and attending local schools. Edward’s occupation on the 1870 Census is molder, likely molding cutlery at the nearby Southington Cutlery Company. Unfortunately, this budding Irish American household was devastated in 1878 when Edward Deegan died leaving his widow and their five children to find work and thrive in their new homeland on their own. This is why Edward’s youngest daughter Sarah is working at the Amon Bradley household in 1880 at the age of 17. Her mother also assisted with the Bradley house chores. In May of 1879, Alice wrote in her diary that “Mrs. Deegan cleaned my room today quite well”. Nearly all the Deegan children were employed and working in a Southington factory in 1880. Sarah’s older sister Catherine then age 22 lists her occupation as “packs hardware”; Mary age 19 lists her occupation as the same. Eldest son Thomas Deegan lists his occupation as “iron molder” and their two youngest boys James age 10 and William age 5 are thankfully unemployed and attending school. Alice Bradley noted that on January 7, 1880 “young Sarah Deegan came last night to live with us”. Alice appears to have been fond of Sarah and mentions here a few times throughout 1880 noting moments making cupcakes together and on Christmas, she wrote that she gave “Sarah Deegan a silk handkerchief.” Throughout the mid to late 1800s many Irish American women in America performed domestic labor and housework to support themselves and raise their families in their new homeland. Especially during the first wave of migration following the 1840s this labor was often all that was available to “foreigners” as noted on Peter Dayle’s church record. Eventually by the turn of the century Irish American laborers were in high demand at local factories with records indicating a strong Irish American workforce at Peck, Stow & Wilcox, Southington Cutlery Company, and Atwater Manufacturing Company. As the Bradley family grew to eventually become the Bradley Barnes household that remains as The Barnes Museum today, Bradley Barnes did not hold his grandfather’s favoritism in hiring Irish American women as servants. Often the Census indicates these positions were held by German or Lithuanian American women. However, the impact that Hannah Deady and Sarah Deegan had during their time here remains in the records of the household that we continue to preserve today, and we celebrate them, their labor, and their strength on this St. Patrick’s Day.

|

|

Visit UsWednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays from 1pm - 5pm

Or by Appointment. Last tour begins one hour prior to close. General Admission - $10

Seniors - $8 Students - $5 Members & Children under 5 - FREE |